GIRL MUSIC 003: KATHLEEN HANNA AND BIKINI KILL | ALONE IN THE BASEMENT, NAKED ON STAGE

"A brief reprieve from sexism--even if it was imperfect and fleeting."

GIRL MUSIC is an independent music newsletter for anyone that loves pretty art and music.

[Editor’s note: All quotes are sourced directly from Rebel Girl, Kathleen Hanna’s memoir.]

venmo/cashapp: junostump

Edits: Becca Stump and Nathan Miller

“I had hair down to my butt in the second grade, but my Mom got sick of washing it, took out her sewing shears, and gave me the ugliest short haircut imaginable. On picture day, I wore a light blue jean jacket with my favorite ladybug t-shirt. The photographer doing my solo shots on the stage of the auditorium had me kneel on one leg with my hand resting on my chin. He then had me lie down in almost the exact pose Burt Reynolds did for the centerfold of Playgirl.

I hadn’t seen him pose any of the other girls this way. It felt weird and interesting. I thought the guy was a serious artist who was pushing the limits until he said, ‘Okay, son, we’re done now.’

I learned that day that adults were giving girls and boys entirely different instructions.”

Kathleen Hanna

This would prove true in the punk scene as well.

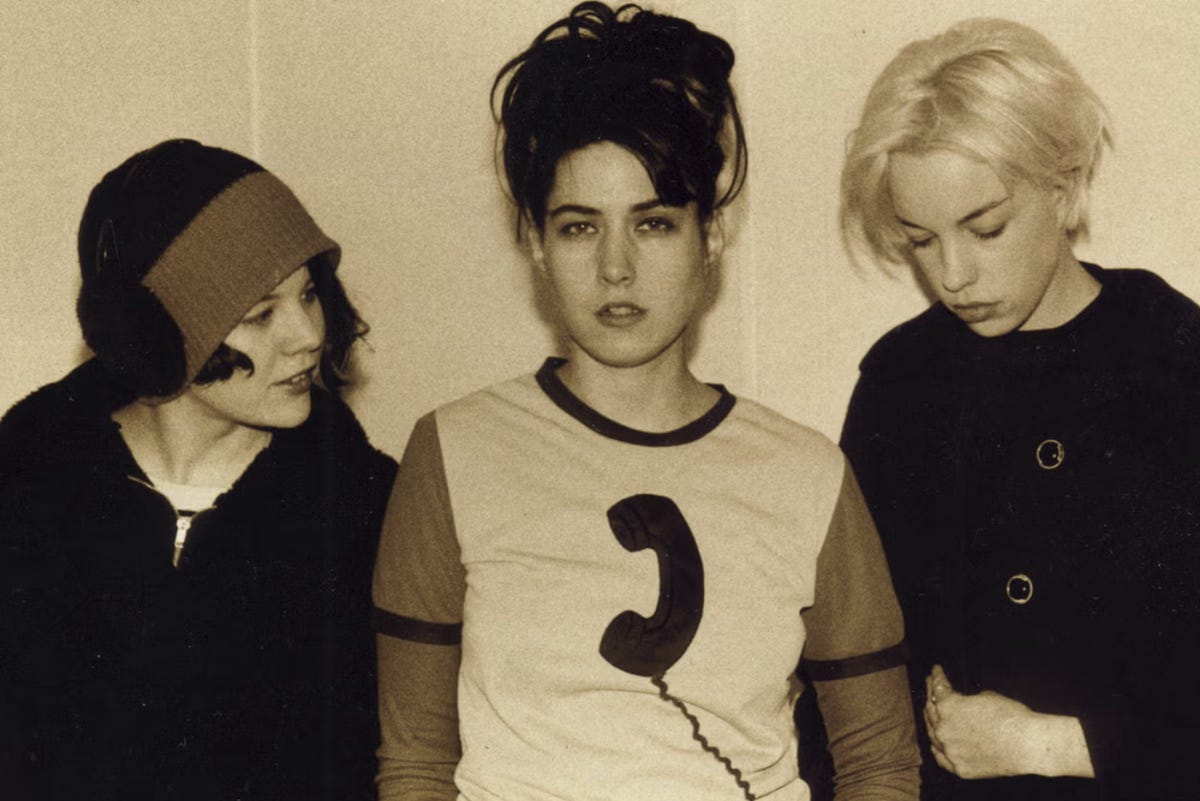

Sixteen years after second grade picture day, BIKINI KILL opened for NIRVANA at the Paramount in Seattle on Halloween 1991, their largest venue ever booked. There were record executives everywhere, DGC Records had arranged for a film crew to capture Nirvana’s performance, and the energy was palpable—chaotic—even if the vibes did feel a little off.

KATHLEEN HANNA tried to focus on how touched she was that KURT COBAIN had asked Bikini Kill to open for Nirvana on such a special, homecoming-sort-of-night, but it was a difficult place to find space for all the feelings—especially since the concert venue didn’t even bother to turn the lights on for Bikini Kill’s performance.

“Opening act Bikini Kill … serves as a reminder that not all Seattle rock bands are ready for the big-time. The band were musically unremarkable, but showed an enthusiasm that helped forgive what they lacked in talent.”

The Seattle Tribune on the performance

Kathleen Hanna didn’t always know she was going to be a punk singer, the leader of a feminist goofball electronic music group, or make the intimate and authentically honest music of Julie Ruin in an isolated apartment. It was always her cosmic, burning passion for activism, poetry, and feminist artists like Kathy Acker that gave Kathleen Hanna the power to become the rebel girl she was always destined to be—the girl who freed and healed herself.

“We're Bikini Kill and we want revolution

Girl-style now!”

The first tour Bikini Kill would embark on after leaving Olympia, Washington would be in a van that had the coziest little nap spot, in the loft above the band’s equipment, resulting from a steady carbon monoxide leak no one knew about.

Kathleen Hanna and Bikini Kill witnessed Nirvana’s rise to superstardom on MTV from a dank motel room, after performing van repairs on the ground of fast food restaurant parking lots.

“I spent most of that tour in Denny’s parking lots on my back trying to tape up the antifreeze hose. We broke down for real in Nebraska and since it was hunting season, no one was around to fix it. We holed up in a $12-a-night motel for a week waiting for the local mechanic to come back and fix our van. We didn’t have MTV in Olympia, but they had it at the hotel, so we watched, half excited and half freaked out, as ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit” played over and over again. Nirvana was becoming the most famous band in the country.”

Hanna had sent postcards to girls whose addresses she had collected at Bikini Kill’s last tour, and each postcard had instructions to “bring other girls” with them.

The postcards read, “Draw Hearts and Stars on your hands and if you see a girl with hearts or stars go ask her if she got a postcard too.”

“The postcards worked: way more women were showing up at our shows. Between songs I would ask if any girls had zines for sale and bring the writers onstage to show their work to the audience. A few times women took to the stage for other reasons, like if a man was fucking with them and they wanted to point him out. I was saying ‘Girls to the front’ at all our shows now.”

It was clear that Bikini Kill was having a visceral reaction with fans and having a meaningful impact on the women that attended the band’s shows—but this also brought its share of violence.

“In Kansas, a super-big dude grabbed me by the shoulders and shook me like I was a rag doll, yelling in my face, ‘you fucking bitch, you’re the reason my girlfriend broke up with me.’

While it was obvious who the real culprit in his breakup was, I stayed silent while our roadie Quigas pulled him off me. I wasn’t saying ‘Girls to the front’ so girls could see us play anymore—we needed them to protect us from guys who wanted to beat us up.”

This first cross country tour came to an abrupt end when the tour van completely broke down in Ohio.

We were stuck, so we called Ian MacKaye [of Fugazi], Kurt [Cobain], and Calvin from K Records and asked if any of them could loan us the $1,000 it would cost to replace our engine. They all turned us down for totally legit reasons, so we left the van at a mechanic’s garage in Ohio.

Tim Green from the Nation of Ulysses, who I was dating, came and picked us up [to give us a ride home.] As we drove into DC, the first thing I saw was a huge ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ billboard by the highway.”

As soon as Kathleen Hanna got back to DC, she started looking for a job immediately, with the goal being to get Bikini Kill back on the road ASAP.

She applied for jobs in used bookstores, restaurants, and other jobs where she could make money and network with other music scene people—but none of these ‘traditional’ employers called her back, so Kathleen Hanna went back to stripping.

“I tried getting jobs in the punk scene world, [like restaurants and book stores], to no avail. I needed to make $1,000 and I only knew one way to do that fast. Luckily, I’d stuffed a thong bikini and my white Kinney heels into a plastic ‘emergency’ bag at the bottom of my orange suitcase. Did I want to go back to stripping? No, but it was something I was good at. My dad had taught me to emotionally play dead to deal with his creepy behavior, and in my own twisted, unhealthy game of ‘lemons to lemonade,’ I turned his abuse into lunchboxes full of cash.

Sometimes [working at the Royal Palace] was like a game of Frogger, if the frog were me and were wearing white Kinney Heels. Challenge: How do I make it across the room to my high-tipping customer [while avoiding the low tipping customer?]

I became pretty popular at the Royal Palace. Since I didn’t drink, I remembered everything my regulars told me. I think they liked having someone consistent to hang out with who at least pretended to be interested in their lives.

I chose thirty-to-forty-year-olds as my regulars because they were the best tippers. I never went anywhere outside the club with a customer, even when I was offered a lot of money to do it.

Then my worlds began to collide.

People in the punk scene found out where I worked.”

The DC punk scene finding out that ‘riot grrrl Kathleen Hanna’ was also ‘stripper to pay her bills Kathleen Hanna’ was too much to resist for many around her at the time, including random people that became aware of her two different jobs and identities.

It was at this point in her life that Kathleen Hanna found herself stripping to ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ while trying not to feel shame, while Shelby, a well-known DC scenester, stood and giggled with her boyfriend.

Things got worse after a picture of the members of Bikini Kill wearing bathing suits (from when the band was on tour in Hawaii) was sold to NEWSWEEK magazine.

Customers from Hanna’s stripping job began to recognize her, calling her by her first name, instead of her stripper name.

It spiraled further when she started seeing strip club regulars appearing at local DC shows.

“When the customer who liked to be called ‘Daddy’ showed up at a Bikini Kill show at DC warehouse, I panicked. When I was dancing at the club, I was a character, but when I was onstage with Bikini Kill, I was an extra-confident version of me. I often used some of the same dance moves I did at the Royal Palace at our shows, but I spun them out into punk moves. In this way I was publicly taking my body back, making the work me disappear so the musician me could sing. I didn’t want ‘Daddy’ to see me vulnerable like that. He only deserved to see me as a checked-out moneymaking doll.”

A few days later, Kathleen Hanna found herself in a conversation with a friend about the disconnect between being a punk feminist and a stripper.

“Ian MacKaye [of Fugazi] wanted to have a conversation about the disconnect between stripping and being a feminist. Apparently, the DC scene did not think my working as a dancer was a good look. I told him it was how I made money and it wasn’t a big deal. I mean, no strip bar customers ever yelled ‘Take it off!’ to me, but I heard that phrase hundreds of times while playing in punk bands.

I told him I didn’t need a lecture from him and that he wasn’t my dad. But secretly he was kind of being a dad in that moment. And I loved knowing that he cared enough to say something.

Maybe I should have been offended that he was asking me to explain myself, but Ian is one of the … most stand-up guys I’ve ever met, and I knew there wasn’t an ounce of malice in his body. I wasn’t stripping as a statement; I just didn’t have a trust fund like so many DC punks did. And thanks to Royal Palace, I’d already made the $1,000 we needed to get the van and start playing shows again.”

The walls continued to close around her when a random man tapped her on the shoulder while she was backstage, preparing to perform at a ‘Rock for Choice’ benefit show.

“Don’t you remember me? I was at the bachelor party on Thursday night,” the man asked her.

She began to pull back from everything. It was hard not to.

JOAN JETT was on the phone, and she wanted to see Bikini Kill perform live. Hanna told Jett Bikini Kill would be performing in New York City in a few months.

Jett said she would be there.

In the few months leading up to this performance, there was a lot of negative press attention for Bikini Kill, making life harder for a band already going through a tumultuous time.

“SPIN Magazine wrote that I bared my breasts at every show (not true) and most articles claimed we hated men because were not like normal girls and had suffered an extreme amount of abuse. Journalists, even women, would write about our bodies and our clothes, but never our songs.

As a twenty-three-year-old with no media experience, it was overwhelming. We were still on Kill Rock Stars, a small independent label started by our friends Slim Moon and Tinuviel Sampson, and we didn’t do interviews with the mainstream press. I’d even stopped doing zine interviews because they had become so painful [and invasive].

Tobi decided that going forward, we should just tour in our pajamas so everyone would leave us the fuck alone, and it worked. Guys still yelled at me onstage, but at least I could go into a pharmacy by myself and no pervs would follow me around. I was in my pajamas in broad daylight carrying a handbag and was definitely not to be fucked with. My life felt so surreal by then that refusing to wear daytime clothes seemed like the only sane response.

We wore pajamas at the show I’d invited Joan Jett to. It was at the Wetlands in New York City. [She] came to see us play that night, just like she said she would. She took me aside after the show and told me she could hear how she would produce us while we were playing. She wanted to make a record with us. The woman who’d produced the Germs’ first album wanted to work with us. She didn’t even ask about the pajama thing. It was like she already knew.”

Kathleen Hanna witnessed many of her spaces begin to change during this time, including the Riot Grrrl meetings she had been attending in DC. Racism and an unwillingness to become anti-racist was consuming many of the white, female punks around Hanna.

She was confused because she had incorrectly assumed other white girls were educating themselves about racism.

“I realized many BIPOC women were as disappointed in white punk feminists as I had been by white male punks. I thought of all the time I’d dealt with men telling me it wasn’t fair to blame them for sexism and then I had [unintentionally] created a workshop where white women blabbed on and on about how they had nothing to do with racism. So many clubs I’d walked into felt like they had invisible ‘White Men Only’ signs on them, and now I’d asked BIPOC women to walk through a similar doorway—only this invisible sign said ‘White Grrrls Only.

I hadn’t seen how so much of our punk feminism was really just white feminism.”

While the DC area had once been a space that had allowed Kathleen to pursue growth, the walls around her were beginning to crumble. The feminist punks at Riot Grrrl meetings were far more interested in remaining stagnant. It was toxic.

What finally pushed Kathleen to leave DC was a stalker breaking into the punk house she was living in—for the second time—in the middle of the night.

Shortly after returning to Washington, Joan Jett worked with Bikini Kill on recording two new songs—‘Demirep’ and ‘New Radio’—and a new recording of ‘Rebel Girl,’ after Jett worked with Hanna on vocal training for hours in the vocal booth.

“[Joan Jett and her manager Kenny Laguna] had me in the vocal booth for hours. They made me do individual lines over [again], coached me about when I could bring the sass, and when I needed to hold off. No one had ever taken me this seriously as singer before. I was soaking up everything said to me.

Bikini Kill was a very raw band and we used our messiness as an invitation, … but Joan reminded us that recording was not neutral; it was art in itself. She showed us that containing our rawness beneath a pop sheen could create an undeniable amount of tension.

I also learned it was okay to have fun in the studio. After I was done with my vocals, I smoked a little weed with Joan and we started trying to remember those singsong slap games we used to play as kids.

Kenny suggested we record one just for fun, so we sat on the floor with a mic over us, stoned as hell, trying to remember ‘Miss Merry Mack,’ [which] we ended up using as the intro to ‘Demirep.’

[We] laughed the whole time we were doing it.

At the end you can hear me say, ‘They’re laughing at us,’ and Joan replies, ‘We’re having fun!”

It was Winter 1993 and Bikini Kill had almost stopped entirely.

The band had already been facing an onslaught of pressures before working with Joan Jett but the punk community was done entirely with Bikini Kill at this point.

“We were currently being called sellouts for making the best thing we’d ever made, the single with Joan. People being mad about it made me feel like I was really outgrowing the naysayers in the punk scene. We’d been playing dangerous shows without security and being yelled at from all sides for too long. It was tough enough dealing with [problems at shows]; we [didn’t even] have time to deal with our individual friendships or musical differences. It just felt too hard to be in Bikini Kill. I was also sick of being in the fishbowl Olympia had become since I’d become indie famous. I couldn’t sit at a coffee shop without someone dropping a zine they’d written about how much they hated me down on the table.

Frustrated, I drove to Portland to find the girl who wrote Snarla in Love, [a zine] a girl named Johanna Fateman gave to me after [a show a few weeks ago].

I knew I wanted to be best friends with whoever wrote it, and I’d heard she worked a combination thrift store/wig shop in a warehouse downtown.”

Johanna lived in an all-women punk house called ‘The Curse.’

It was chaotic, messy, and even had homemade punk walls in the living room to yield an extra bedroom to rent.

Kathleen Hanna spent time with artists, musicians, writers, and “just generally sweet, loving people who liked to make shit happen.”

“I knew separatism wasn’t for everyone, but it was something I needed in that moment.

The real draw to Portland for me was Johanna. She was making these massive abstract paintings at the time and going to Reed College. She also had a side business cutting and dying hair, so we’d walk around the neighborhood hanging up flyers, chitchatting like normal friends.

Jo was the first person I’d met in a long time who I trusted. She was my peer, not a fan. She couldn’t have given a shit about Bikini Kill, though she said she loved ‘the energy’ of the shows.

Every day I got to know her, I loved her more and more. She was one of the smartest people I’d ever met but wasn’t a snob about it.

Johanna’s friendship was what really brought me back to life.”

Kathleen Hanna flew to LA to appear in the music video for ‘Bull in the Heather’ with SONIC YOUTH. She almost didn’t agree to the appearance because she thought people might respond badly to her if she appeared in a mainstream video on MTV. She was already dealing with enough. But then she thought about how fucking cool it would be—and how badly she needed the five hundred dollars for appearing in the video.

After the video shoot, she drove to Olympia to practice with Bikini Kill, sleeping on a futon in the Kill Rock Stars record label office.

Slim Moon came into the office, early and on a Saturday, to carefully deliver the tragic news that Kurt Cobain, a friend to both of them, had passed away.

“I got up and walked over to the window. It was the same view I’d seen a million times, another gray Pacific Northwest day. Only this was the worst. This was the worst day.”

Bikini Kill started playing together with regularity after Kurt’s passing, though the band didn’t really talk about or deal with their feelings and the situation. The band just picked up the pieces and started moving forward again.

Riot Grrrl groups and other corners of Hanna’s life were closing in around her as she was trying to process everything … but she just didn’t have the energy to focus on anything, let alone everything.

Lollapalooza 1995 brought good and bad times—with Sonic Youth and Courtney Love respectively—but three people close to Kathleen Hanna passed away—all within three days—just a few months later.

“Three deaths in three days. Everything felt sad and gray and untenable.

I was in the kind of funk where it was absolutely impossible for me to wear anything other than super-dirty pajamas.”

Working with a former rapist in the studio while Bikini Kill wrapped up production 1995’s Reject All American was too overwhelming for Kathleen Hanna, especially since she was still processing the three different deaths of her loved ones that had just passed.

Once the recording process was finished and Kathleen had finished chain-smoking cigarettes, she went shopping for her apartment with Kathi. This is when she opened up to her friend and band-mate about the person in the studio who had raped her.

“Kathi and I were sitting the parking lot at Target when I told her about Darren. I was worried that she wouldn’t believe me, because everyone loved Darren, and no one would’ve ever guessed he was capable of rape. She was shocked, but she believed me right away. She said she felt terrible I’d stayed silent for so long, especially at the recording studio, but she understood. I asked her if she could tell Tobi for me and she said yes. When Kathi reached across the front seat and hugged me, I felt like I’d been given clemency for a crime I didn’t even commit.”

Bikini Kill went on to enjoy a warm break in Australia in January 1996, when the Beastie Boys invited them to play a festival tour.

“I was sure Tobi and Kathi would think it was sellout move, but it was freezing cold in Olympia in January, and it would be summertime in Australia. We had all been through a lot of death and sadness lately, and something needed to change.”

During the festival, Kathleen would develop a friendship with Adam Horovitz of the Beastie Boys.

Months later, after the festival, Adam sees a drum machine that’s usually over five hundred bucks in New York that’s only forty bucks. He insists that Kathleen purchase the drum set because she will love it.

Adam had no idea he had just encouraged her to purchase the literal instrument that would ultimately help her finish healing. The drum machine that would make way for Julie Ruin.

But first things got worse. Much worse.

“I got a letter calling me a terrible sellout feminist and a fascist, among other things, which was nothing new. But when I looked in the corner, I saw it was from the PO box I’d rented when I lived in DC and let Riot Grrrl use. Seeing my old address in the corner of a piece of hate mail made me feel like I’d sent the letter to myself.

I started getting sick again like I had in high school. My fever hit 105 and I was barely able to call my mom, who drove all the way from Portland to take me to the emergency room. Just like when I was a teenager, they diagnosed me with ‘some kind of autoimmune illness,’ but they weren’t sure which one. I spent the night in the hospital with my mom holding my hand as the nurses tried to get my temperature to dip below 104.

While I recovered, I thought about how stress had always precipitated my illnesses. I got sick after my dad said he wished I was dead. I got sick when the class president was stalking me. I got sick after Alex raped me at that dumb party. And while I knew I couldn’t stop life from being stressful, I also knew something needed to change. I decided I would journal my way out of caring what some random woman … or anyone else thought of me. I needed to find a way out of the horror movie I was in.”

I AM JULIE RUIN

Bikini Kill was in shambles. Everyone in and around the band was still struggling with Kurt Cobain’s death when another friend passed away from a drug overdose.

Everything was demoralizing and difficult.

Kathleen tried getting Bikini Kill to work on some music on her drum machine and keyboard, but there just wasn’t any interest or motivation—so she kept writing on her own.

In the end, it was ultimately what saved and freed Kathleen Hanna’s soul from the grip of the world intent on spending every cent of her.

"I’d clung to being understood for so long that I’d lost sigh of poetry and how sound could convey meaning. I was so excited to be making stuff without a big mission statement. The [only] problem [I had was] I couldn’t fit all my ideas into four tracks.”

Kathleen had been living in an apartment above a drug dealer’s house, freed from the music closet at her last place, and now able to experiment with music at all hours of the night. Who was going to call the cops? Her downstairs drug dealing neighbor?

She purchased an eight-track off of eBay and then all of her ideas flowed out like a broken dam of water.

She wrote songs about witnessing oppressive attitudes take over once liberating punk spaces, but she also wrote lyrics about how she loved herself, how she thought she was awesome, and how she was worth loving—scrunchie in her hair and all.

“I was in control of the means of production with no interference, and it felt so fucking powerful. I didn’t’ have to wait for my band to practice anymore—I could make my songs myself. It was the first time I recorded as I wrote, which meant I could wake up in the middle of the night with any ideas and record it at three a.m.

Trust wasn’t something I had a backpack or even a clutch bag full of at the time, but I trusted that eight-track. It was a time machine taking me back to who I was before Darren raped me and before I became the de facto leader of Riot Grrrl.

I decided to make the record from the perspective of who I wanted to be instead of who I was, and this person’s name was Julie Ruin.”

Kathleen worked day and night on her passion project, the music that would become the first Julie Ruin album. When she wasn’t putting down instrumentals, vocals, or mixing in her apartment, she was working out lyrics and blocking out the structure of songs.

But then there was something peeking at her through her vision one night, when Kathleen felt like she was being watched.

She looked out the window, above where she was working, and that’s when she saw a ladder going up the side of the gym across the street from her apartment.

And then she saw something even worse: a man laying on the roof and staring at her through binoculars.

She took precautions, but ultimately had to make the decision between living in apartment where a future rape could occur, or living in her old apartment, a place where she had already been raped.

Kathleen made the difficult but very necessary decision to move back into Apartment number five, the only other apartment available where she could be safe and finish working on her music.

“I immediately painted every wall green so it looked different from when ‘the thing’ happened. I lay in bed depressed and watched videotapes Slim loaned me.

Paul, who had taught me to use the eight-track, worked with me to add missing bits and baubles to the songs and to engineer the ones I hadn’t mixed yet.

I still had a song in me that needed to come out. It was about Darren and included the lyrics:

‘You can tell anyone anything you want, / But if you’re gonna talk about how I deserved what you did / You can look now cuz I’m gone, I’m gone.’

I called it ‘Apt. #5.’

This was when Julie Ruin saved my emotional life. I xeroxed myself as ‘Julie,’ surrounded by puppies. I glued her on top of a luxurious house interior, while I lived inside the apartment my best friend had raped me in. She was stronger than me, more experimental, and she was happy.”

Therapy and pursuing additional healing helped Kathleen realize a few things. One was, she needed to leave Olympia. The second thing was that her Tobi needed a break. They were close friends that deeply cared for each other, but they were also both too exhausted to be there for themselves right now, let alone each other.

“Tobi and I had been estranged for a while. [We should have made plans to meet and talk in person but instead] we ended up shoving endless letters under each other’s doors. [My saving grace at the time] was working on my Julie Ruin album art.

I stopped writing to Tobi and got my first therapist. She said Tobi and I had developed a dysfunctional dynamic that we were both too exhausted to fix.

I couldn’t keep doing the band if we coldn’t work things out, so all signs were pointing to toward me getting the fuck out of that apartment, out of my stressful band, and out of Olympia altogether.”

Hanna went back to Portland to finish the mixing and mastering process on Julie Ruin, which Kill Rock Stars had agreed to pay for … but it just … wasn’t working.

Likely due to a combination of imposter syndrome and the engineers in the studio just weren’t getting it. At one point Kathleen Hanna was even asked to go get coffee for the men in the room … while they worked on … her album.

“When I listened to it at home, I hated how it sounded. I wasn’t sure if mastering had ruined it or if my record just sucked. I put the final mix [into boxes], unsure if I’d ever put it out or even listen to it again”

Hanna left Olympia after a pancake breakfast with Kathi Wilcox. They discussed how maybe Bikini Kill had run its course, and how that was okay.

As they talked and Kathleen listened to her, she “felt every muscle in [her] body unclench.”

“ … My North Fucking Star.”

Kathleen left Olympia and headed for North Carolina—because it’s where Tammy Rae was, and that’s where she always said she’d go if she ever left Olympia for another home.

“I moved into the attic room of the house [Tammy Rae] shared with her girlfriend Kaia Wilson. I heard that Chris Stamey, who was in ‘the dBs’, one of my favorite power pop bands, had a recording studio in his house nearby, so I called him.

I wanted to remaster the Julie Ruin record. I had to use my own money this time, but he let me pay in installments.

Chris totally got me, and more important, he got the record. He was metitculous and professional and a joy to be around. He wiped my other mastering experiences off the board. He had a vision for my record, and I had one, and between those two visions we made something better than either of us could have alone.

It was a happy form of tension I wanted, and Chris made it happen. I had such a great time with him that when I got back to my attic room, I started writing more songs”

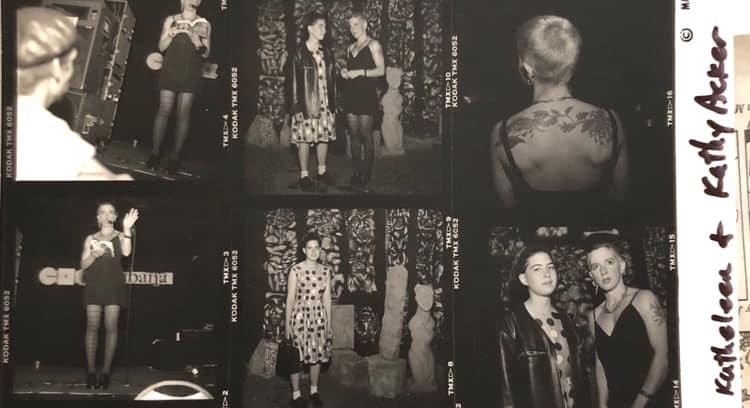

Kathleen Hanna was growing and continuing her healing, while pusuing the creation of more art, until the woman who inspired her, the woman responsible for her ever being in a rock band to begin with, Kathy Acker, passed away.

“My face went gray. The queen of everything, the person who spurred me to become cool enough to be her peer, who gave me guidance, who told me to start a band, was fucking gone. The world lost one of its most brilliant writers that day. A genius feminist pirate, my north fucking star.

I’d last seen Kathy at a Bikini Kill show in Spokane, Washington. We hung out afterward and she said she loved our band. I reminded her she was the reason I was even in a band and she seemed genuinely touched, but not like she remembered telling me to do it.”

Kathleen Hanna had first met Kathy Acker when she was nearly finished at Evergreen and “beginning to worry [she] would leave college without the ability to write anything more coherent than a spoken-word piece.”

It was then that she discovered and read Kathy Acker’s ‘Blood and Guts in High School,’ which really impacted her.

She devoured all of Acker’s books and texts. When it became time to write an essay about someone whose art affected her for a writing class, Hanna chose Acker.

A short while later, Hanna was able to attend a writer’s workshop at the center on Contemporary Art in Seattle that Acker was leading.

This would be one of the most pivotal moments in Hanna’s life, a conversation that would frame her path of activism in a way where she would know she would be heard.

“I was shaking when she called my name [but] I took a deep breath and reminded myself I wasn’t going to waste my five minutes with Kathy Acker

‘What have you been doing in Olympia, Washington,” she asked.

‘Spoken word,’ I said.

‘Why do you want to write,’ she asked.

I didn’t know what to say but instead of making something up like I usually did, I sat quiet for a minute [before answering].

I opened my mouth and said, ‘Because no one has listened to me my whole life and I really want to be heard.’

[Acker] appraised me for a second and then said, ‘You should start a band. Most people go outside and smoke when someone gets up to do spoken word, but people wanna see bands.”

Later that night, Kathleen saw her first punk show: a sold out Fugazi show. Kathleen Hanna was lingering around the side door when Tobi Vail recognized her and helped her squeeze into the audience.

The two girls barely knew each other at the time. Vail was in a local band called GO TEAM. But it was these two moments close togehter, this affirmation of punk rock, feminism, friendship, and female idols that pushed Kathleen Hanna towards her destiny.

Now in 1997, decades away from that moment, Hanna couldn’t help but reflect on how much Acker had influenced her life, as a woman and an artist.

“Acker may have seen this as a brief encounter with another fan whose life she’d changed, but I saw it as a pin in an invisible map that would someday lead me to being smart and seasoned enough to spend real time with her.

I wanted to cook and clean for Kathy when she was too old to do it for herself.

I wanted to pay her back for the life she’d given me.

But now I was just a woman who’d bought an air conditioner at Home Depot, sitting in a car crying [after learning from Tammy Rae that Acker had passed away].”

Kathleen Hanna resigned from Bikini Kill on February 2, 1998, after realizing she’d approached feminism from the wrong angle.

“I knew sisterhood was a way more complicated concept than I thought it was when I was nineteen, and I needed to reassess what I was doing.”

Kathleen started rereading feminist texts from sixties and seventies, which helped her reevaluate everything she thought she had understood already.

This included Jo Freeman’s’ ‘Trashing: The Dark Side of Sisterhood’ (from a 1976 issue of Ms. magazine), Elaine Brown’s ‘A Taste of Power,’ and Alice Echols’s ‘Daring to Be Bad.’

“I came to realize that while I’d been an instigator, I wasn’t really an activist, I was a musician who worked on the cultural front.”

It was at this time in Kathleen Hanna’s life that she got a day job doing data entry, enjoyed cheesecake and time with Adam—when she could afford the bus trip to travel to NYC from Manhattan. This was a time of great reflection and growth, before Kathleen Hanna would once again find herself at the center of another feminist music scene.

It was 1998. Kathleen was living with Adam in New York City. She had a publicist and was traveling through the city to speak with journalists about her art and music. She was doing it. And she was ready to perform the music of Julie Ruin live.

Kathleen hit up her friend and former roommate, Johanna Fateman, to work on practicing the music of Julie Ruin live.

But then her sampler she had used before was broken and it just felt like it was time to write new music.

Plus, it felt like Kathleen was ready to be happy.

“Jo suggested we stop writing about all of the baad stuff we’d encountered and said ‘we should write about the good stuff,’ and it felt like a radical concept.

It was time to get over myself and all the scene poolitics and just say ‘Thank you.”

LE TIGRE

The work on the first LE TIGRE album was collabrative, exciting, and fun.

The first tour had small audiences and Kathleen was back to sleeping on people’s floors, but she didn’t want any of it to end.

“I had found my songwriting partner in Johanna and was in love with our band.”

Le Tigre was a healing experience for Kathleen Hanna, allowing her to further embrace her identity authentically, even allowing her retrain her singing and breath control to be done in a way that was more healthy for her, during performances and her daily life.

It allowed her to heal and grieve the time and pieces of herself she had lost, just like she had tried to help so many girls do when she listened to stories of their abuse after Bikini Kill shows.

The lyrics of Le Tigre’s music were feminism in a different kind of way than Kathleen had gotten to do with her previous music, this time it was freeing for her as well.

“Johanna’s catchy feminist garage rock anthem ‘Mediocrity Rules’ [was performed live] in front of the words ‘Behind the veil of male expertise lies the magic world of our unmade art.’

Maybe the struggle for language was the moment we were trapped in. Why were we always supposed to answer ignorant questions with thoughtful, articulate answers?

Why were we always explaining ourselves? Maybe that’s what third wave [feminism] was all about: speaking back to power with sounds that didn’t always make sense.”

Le Tigre was growing, touring internationally, and very much a part of the feminist electronic music scene, but Kathleen was beginning to feel exhausted again.

Hanna realized needed a break, but she started to lose her language—her words—and the pieces of herself that allowed her to keep going.

She started to get sick again. Just like right before she was making the first Julie Ruin album.

First it seemed like the flu, then bronchitis, but it was always something—and she just couldn’t keep going on—even if Le Tigre was on a worldwide tour promoting their third album.

“When my bandmates came to check on me [in my hotel room], I was crying inconsolably. I needed to get off the tour even if I had to chop one of my toes off to do it. I kept talking about the toe-chopping thing and then felt embarrassedand tried to take it back and said everything was fine.

Five minutes later I was talking gibberish again and feeling utterly hopeless.

Even as it was happening, I could see how weird I was acting, but I was unable to stop. It may’ve seemed like I was stammering because I was crying, but really the crying was because every time I tried to speak, my words came out slurred and confused.

The harder I tried to say a full sentence, the worse it would sound.

As the mixed-up half sentences hit my ears, I grew more and more frantic.

I was losing language.”

Her wedding to Adam lifted her mysterious illness, like other warm parts of her life had done in the past. She tried to get pregnant and was successful but there was a tragic loss of the baby during the first trimester.

The grief took time to process and was really hard. When Kathleen recovered as much as one can from something like that, she put her energy back into being properly diagnosed while archiving her work.

And then in September 2010, she got the proper diagnosis to begin treating her mysterious illnesses she had been dealing with for so much of her life. It was Lyme Disease, and it being missed and never dealt with had allowed it to spread to her muscles, blood, and brain. Stress would cause flareups that would ultimately result in the strong symptoms showing up when they did.

Kathi Wilcox and Adam Horovitz both helped Kathleen on her healing journey for the two years it took. It took countless appointments, re-learning to speak, surviving endless seizures while she regained control of all of her muscle functions.

It was not an easy process for her but she got closer to herself, and learned to love herself, while she healed all of the way.

Kathleen Hanna was able to get back on her feet and be the strongest version of herself that she could ever be.

She was a changed woman and a new woman—all at once—but she was still the rebel girl she always was, only now she could also be that rebel for herself.

And she was able to continue helping others, performing music, and creating art, while also enjoying her new and healed life.

“I didn’t leave either of my bands with much money, but I did leave with a name and, whether I liked it or not, a reputation as a figurehead in the punk feminist scene. this meant I was often approached to give talks, and since I was feeling better, I hired a booking agent who could help me turn that into a part-time job.

Fame had once been my enem, but now it was providing me with a steady income and the creative outlet I was craving.

Lectures allowed me to talk about how I made art, the techniques I used as a songwriter, and all the other things no one ever asked me about. I also got to talk about my experience as a “famous feminist” and how I was constantly confronted with people’s disappointments in me, whether they thought I had sold out because I was in a Sonic Youth video or was a bad feminist because I’d been a sex worker.

People would often exaggerate any compromises I made for economic reasons as proof that I was not authentic. But I countered these bogus arguments by moving past notions ‘purity’ and learning how to accept real critique as a gift.”

I [got to talk] about how I thought Riot Grrrl went wrong and pointed people in the direction of writers like Mimi Thi Nguyen, a writer who produced several zines, including ‘Slander',’ that contained writing about how white middle-class assumptions kept the Riot Grrrl gate closed to so many girls and women of color.

I was also able to talk about the contributions of Lelie Mah, Martin Sorrondeguy, Vaginal Creme Davis, Ramdasha Bikceem, Selena Wahng, Iraya Robles, Yalan Papillons, Carlos Cañedo, Lori Barbero, Wendy Yao, and many other BIPOC people [who had contributed to] Riot Grrrl and punk in general.

Getting to introduce young people to the work that so many of us did so long ago made the difficult things I’d gone through feel worth it.

It was healing to be honest about my failures and successes.

And [whenever I’m] asked if I [want] a ‘Riot Grrrl Revival,’ I always [say] no.

‘Take the good stuff into the future and leave the lack of intersectionality behind.

But don’t call it Riot Grrrl, because it has bad connotations for a lot of people.

You all can think of a better name!”

Kathleen Hanna grew up being called a ‘slut’ by her father and everyone around her.

Shame and boxes are something so many marginalized people deal with our often cruel society, but we can take our experiences and create art to light the path forward for those around us, and those that will eventually walk in our foot steps.

Kathleen Hanna is an artist and the front woman of multiple bands, but she’s also a woman who has invested time into healing herself, and that’s something we can all take inspiration from, whether we listen to Bikini Kill, Julie Ruin, Le Tigre, or some other kind of girl music.

Six essential tracks from KATHLEEN HANNA’S discography:

More from KATHLEEN HANNA:

DAN RATHER interviewing KATHLEEN HANNA and ADAM HOROVITZ (2021)

KATHLEEN HANNA talking about SMELLS LIKE TEEN SPIRIT and KURT COBAIN (2010)

Trailer for The Punk Singer (a film about KATHLEEN HANNA released in 2013)

notable performances from KATHLEEN HANNA’S life:

BIKINI KILL - ‘Rebel Girl’ / LIVE on The Late Show (2024)

BIKINI KILL playing a full show in Los Angeles (1993)

BIKINI KILL - ‘Rebel Girl’ at Yale University (1996)

BIKINI KILL performing at Riot Fest (2019)

LE TIGRE - TKO on Conan (2005)

THE JULIE RUIN - HA HA HA at Pitchfork Music Festival (2015)

Consider subscribing so you don’t miss any GIRL MUSIC